Spirit of Acorn . com

Creating a small keel yacht designed for the soul, not the ego

Skyline of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia from Spirit of Acorn

Before You Let Her Go by C.H. (Bob) Andrews

Just as some people try to find their roots in ancestral archives, I recently completed a seven-year search for an old and trusted friend and once proud possession, a lovely little Acorn sloop which had been mine from 1965 to 1971.

This experience has led me to believe that a lot of forethought should go into such an important move as selling; perhaps as much , if not more, than the original purchase. Because often a sailor has invested much of himself in learning his boat, modifying her, becoming comfortable with her habits. And that may be an investment he cannot easily recoup.

Why do we part company with our boats to begin with? There seem to be almost as many reasons as there are myriad craft plying the world's waters. The obvious reasons are financial, marital, changes in occupation and location, the lure of a bigger boat or different rig; or, if you are a racing buff, the IOR rule changes, which can turn good class boats into morphodytes.

In more than 30 years' cruising, I have run the gamut of rigs and sizes of sailboats, hating and loving them all in varying degrees. But the disenchantment was seldom the fault of any one boat. Either I fell in love with a new one, or failed to adequately learn the ways of the old one, or started a modification program, and didn't follow it through to a logical conclusion. In one instance I wound up with a lovely big ketch at a bargain price, but found the joy of ownership soon dimmed by the rapidly mounting costs of owning her. On my family list of priorities, sailing fitted in somewhere down the line, not at the top. So I had to become realistic and practical. Out of all these boats and my experiences with them, the little Acorn stuck in my mind. I had always loved her, perhaps too much, as I later discovered.

I had bought her in 1965 from a Stanford University professor who was going on sabbatical to Europe. Built in 1950 by Easom Boat Works in San Francisco, she had a colorful history. The hull, No. 11, had been carefully laid up with Port Orford cedar planking over oak frames by Mr. Easom and his two sons. So enamored of her were the boys that they "borrowed" some cherished mahogany from their father's precious stockpile for the cabin house and cockpit and went beyond the one-design specs in beefing up things like the bronze hardware. She was a beauty. Easom watched this with a true Scot's eye and said, "Boys, you'd better not put anything more into that little boat or we're going to be behind the eight ball". The sons, surveying her neat little tumblehome and saucy counter, replied, "When she races on the Bay, everybody will be behind the Eight Ball"; And that became her name.

True to advance billing, EIGHT BALL won 27 consecutive races, setting a record for one-design boats. Many times she raced out to the Farralones in miserable weather, and when I bought her she had the original mainsail, without reef points! Like the famed Bird boats of San Francisco, the Acorns carried all their laundry in fair weather and foul. (I still have that mainsail, for luck).

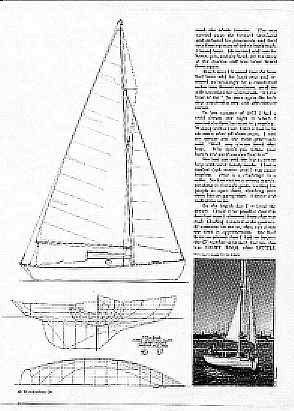

For those interested in measurements, she is 19'2", on deck, 17' LWL, 6'6"; beam, 3'9"; draft, with

moderately cutaway forefoot and full keel carrying 1,200 lbs of lead down where it does the most good. She displaces 3,000 lbs empty and has a 3/4 rig carrying 185 square feet of sail. Her hollow spruce mast (30'6") steps onto a big ironwood shoe spanning five frames, so she is hell for stout. She carries a spinnaker along with a new-style combination genoa/drifter/spinnaker which requires no pole but which pulls like mad off the wind.

She is built for heavy weather with a small self-bailing cockpit and a strong bridge deck, which also

keeps seawater from getting below.

I re-rigged all halyards leading aft for solo work and set up downhauls so as to douse sails instantly

without leaving the cockpit, where I am usually buckled to a big pad eye through bolted to the bulkhead. If I go, the boat has to come with me, or vice versa.

Oddly, this peanut craft easily tops 6 to 7 knots in a 20 mph blow, disproving that old waterline-speed

ratio theory. Some boats do and some don't. But even a cruising bum likes his boat to get up and go

once in awhile.

This unique little boat was designed by Jim DeWitt the elder in 1934 as a class boat, which earned it the appelation of "The Biggest Little Boat on the Bay" in the book Sailing Classes of San Francisco Bay, now a rare possession of the St. Francis Yacht Club and long out of print. (The younger Jim DeWitt is now owner of DeWitt Sailmakers). Acorns raced against Bears, Folkboats, IC's and all manner of small craft, but their real potential as performing cruisers was never fulfilled. Fibreglass arrived, and with it came the boats with greater interior space and higher freeboard, a mixed bag of blessings.

Some of us purists cling tenaciously to the ancient theorem that the measure of an ocean-going sailor is directly counter to the height of his cabin and the size of his ports. The Acorn has what might be termed loosely as crawling headroom, and it resembles 12th century slits in the turrets of a fortress. Liveaboards may view this arrangement with distaste, but for heavy weather sailing, and even anchoring, there is a great sense of womb security in riding out a storm below. If you are tossed only a matter of inches it is less painful than four or five feet, and definately safer than ducking flying objects like galley knives.

Changing clothes is accomplished by lying on the cabin sole. Cooking is done in a crouch or on the knees, so I have yielded to my wife's entreaties to carpet the interior.

There are compensations for all this spartanship. She beats almost into the eye of the

wind, and her low profile/fine entry make it remarkably comfortable going into the short

choppy seas of the West Coast.

After all this eulogizing, you ask, why did I sell her in the first place? It was shamefully

stupid. In a fit of pique following a domestic scene with boat playing the role of mistress,

and loving wife saying, "All you ever think about is that %&!* boat," I put her up for sale.

Months later, restless and disconsolate, I found a nice old sloop which needed tender

loving care, and for several years devoted myself to making her over into a respectable

cutter and a stout singlehander. A larger cutter then caught my eye and I went through

the trauma , once again, of buying and selling. These, too, were wood boats, mainly

because I am a masochistic fool who likes to work on boats as well as sail them.

And finances being what they are, I cannot aford a new Bob Perry or Lyle Hess design

much as I'd like one.

So, in the years following 1971, I would often wander through the marinas of southern

California looking for the familiar white spruce mast with the jumper struts and the

saucy crane head. Some day, I thought, if I ever see that Acorn again, what will I do?

The man I had sold her to had immediately embarked on a ambitious cruise,

destination Alaska. (I has seriously considered Hawaii, but Alaska? Good Lord!).

Somewhere off the coast of Oregon he ran into a brutal storm. He had a fire on board

with the kerosene stove which totally blackened the whole interior. The seas carried away the forward ventilator and reduced his possessions and food to a floating mass of debris bunk-high, I heard later. He turned and ran for home, job, and dry land, left the sloop at the marina and was never heard from again.

Much later I learned that the boat had been sold for back rent and restored painstakingly by a committed sailor into Bristol condition, until his wife uncorked her ultimatum, "It's the boat or me." So once again the little ship acquired a new and affectionate owner.

In the late summer of 1977 I had a vivid dream one night in which I spotted the familiar mast in a marina. Waking with a start, I felt it had to be an omen after all those years. I told my spouse and she most generously said, "Well, you always loved that boat. Why don't you follow your hunch and see if you can find her?"

We had just sold the big cutter to help with some family needs. I had a modest cash reserve and I was once again boatless. That is a challenge to the sailor. So I set out on a serious search, sneaking in through gates, waiting for people to open them, climbing over them like an aging thief. I drove and walked for miles.

On the fourth day I re-lived the dream. Could it be possible that this familiar mast I observed from afar was real? Chafing, I waited at the gate until someone let me in, then ran down the dock in apprehension. She had been so altered that I had to inspect the CF number to be sure, but yes, this was EIGHT BALL alias LITTLE JOSIE alias how many other names, heaven only knows.

And I, a grown man, stood gazing at her with tears streaming down my face in a welling-up of remembrances. Days and nights andweeks on end sailing the Pacific with her as my only companion. Being down below reading or sleeping or making soup while she obediently held her course with a piece of shock cord at the helm.

Now she looked unbelievably small. Had I done all that cruising in this tiny craft and come home again and again, safely?

With trembling hands I penned a note to the owner on the back of an envelope and stuffed it through the hatchway. I told him this once had been my boat and asked him if he would consider selling it to me now.

Next evening he called, astounded at my story. Did I really want her back that badly? Of course. When your heart is on your sleeve, you're in no mood to dicker. We met at the harbor the next day and he described how fond he was of her but that his family was simply too tall and too numerous to share her space-capsule accomodations. They wanted a bigger boat.

So it was done.

Now I am the soul of content, hoping that this time I can stay that way. Why is it that men must forever be questing and searching, and malcontent? I had to go through all of this to come back to dead center. I should know by now that every boat has virtues and faults alike, that each selection we make is a compromise. Rising costs of dock fees, parts, equipment all have a bearing on what we sail and what we logically should stick with. True, some bigger boats are a good investment because they gain in value as labor and materials soar to new heights.

It is strange. I am no longer a young man, but the fires of adventure still smolder within, and I still dream the improbable dreams of faraway shores and the lengthy sojourns on the ocean that renew the soul.

It may yet pass that I can write for you some interesting accounts of how LITTLE JOSIE and I made it across the Pacific to legendary lands that so few of us are privileged to see. Having once sold my sextant and the Sailing Directions of the Pacific Ocean doesn't mean that I have truly given up. One must never give up. You have to keep the dream alive, for that is the elixir which sustains us through all the other impediments of life.

One day I will own another sextent and a good weather radio, and I will send you an adventurous account from the lands below, from a very small and adequate boat I have learned to trust, and I will be treating her with the deferential and circumspect devotion to which a lovely little lady is entitled.

May you also find the boat of your dreams and hold onto her for dear life. It may mean making the most of what you already have, but in an ensuing article I will try to advise you on how to do just that.

C.H. (Bob) Andrews is a writer, former newspaper publisher, and a veteran of much solo ocean sailing. His ambition is to sail LITTLE JO to Australia. "She'll do it," he says, "the biggest obstacle is me."

Just as some people try to find their roots in ancestral archives, I recently completed a seven-year search for an old and trusted friend and once proud possession, a lovely little Acorn sloop which had been mine from 1965 to 1971.

This experience has led me to believe that a lot of forethought should go into such an important move as selling; perhaps as much , if not more, than the original purchase. Because often a sailor has invested much of himself in learning his boat, modifying her, becoming comfortable with her habits. And that may be an investment he cannot easily recoup.

Why do we part company with our boats to begin with? There seem to be almost as many reasons as there are myriad craft plying the world's waters. The obvious reasons are financial, marital, changes in occupation and location, the lure of a bigger boat or different rig; or, if you are a racing buff, the IOR rule changes, which can turn good class boats into morphodytes.

In more than 30 years' cruising, I have run the gamut of rigs and sizes of sailboats, hating and loving them all in varying degrees. But the disenchantment was seldom the fault of any one boat. Either I fell in love with a new one, or failed to adequately learn the ways of the old one, or started a modification program, and didn't follow it through to a logical conclusion. In one instance I wound up with a lovely big ketch at a bargain price, but found the joy of ownership soon dimmed by the rapidly mounting costs of owning her. On my family list of priorities, sailing fitted in somewhere down the line, not at the top. So I had to become realistic and practical. Out of all these boats and my experiences with them, the little Acorn stuck in my mind. I had always loved her, perhaps too much, as I later discovered.

I had bought her in 1965 from a Stanford University professor who was going on sabbatical to Europe. Built in 1950 by Easom Boat Works in San Francisco, she had a colorful history. The hull, No. 11, had been carefully laid up with Port Orford cedar planking over oak frames by Mr. Easom and his two sons. So enamored of her were the boys that they "borrowed" some cherished mahogany from their father's precious stockpile for the cabin house and cockpit and went beyond the one-design specs in beefing up things like the bronze hardware. She was a beauty. Easom watched this with a true Scot's eye and said, "Boys, you'd better not put anything more into that little boat or we're going to be behind the eight ball". The sons, surveying her neat little tumblehome and saucy counter, replied, "When she races on the Bay, everybody will be behind the Eight Ball"; And that became her name.

True to advance billing, EIGHT BALL won 27 consecutive races, setting a record for one-design boats. Many times she raced out to the Farralones in miserable weather, and when I bought her she had the original mainsail, without reef points! Like the famed Bird boats of San Francisco, the Acorns carried all their laundry in fair weather and foul. (I still have that mainsail, for luck).

For those interested in measurements, she is 19'2", on deck, 17' LWL, 6'6"; beam, 3'9"; draft, with

moderately cutaway forefoot and full keel carrying 1,200 lbs of lead down where it does the most good. She displaces 3,000 lbs empty and has a 3/4 rig carrying 185 square feet of sail. Her hollow spruce mast (30'6") steps onto a big ironwood shoe spanning five frames, so she is hell for stout. She carries a spinnaker along with a new-style combination genoa/drifter/spinnaker which requires no pole but which pulls like mad off the wind.

She is built for heavy weather with a small self-bailing cockpit and a strong bridge deck, which also

keeps seawater from getting below.

I re-rigged all halyards leading aft for solo work and set up downhauls so as to douse sails instantly

without leaving the cockpit, where I am usually buckled to a big pad eye through bolted to the bulkhead. If I go, the boat has to come with me, or vice versa.

Oddly, this peanut craft easily tops 6 to 7 knots in a 20 mph blow, disproving that old waterline-speed

ratio theory. Some boats do and some don't. But even a cruising bum likes his boat to get up and go

once in awhile.

This unique little boat was designed by Jim DeWitt the elder in 1934 as a class boat, which earned it the appelation of "The Biggest Little Boat on the Bay" in the book Sailing Classes of San Francisco Bay, now a rare possession of the St. Francis Yacht Club and long out of print. (The younger Jim DeWitt is now owner of DeWitt Sailmakers). Acorns raced against Bears, Folkboats, IC's and all manner of small craft, but their real potential as performing cruisers was never fulfilled. Fibreglass arrived, and with it came the boats with greater interior space and higher freeboard, a mixed bag of blessings.

Some of us purists cling tenaciously to the ancient theorem that the measure of an ocean-going sailor is directly counter to the height of his cabin and the size of his ports. The Acorn has what might be termed loosely as crawling headroom, and it resembles 12th century slits in the turrets of a fortress. Liveaboards may view this arrangement with distaste, but for heavy weather sailing, and even anchoring, there is a great sense of womb security in riding out a storm below. If you are tossed only a matter of inches it is less painful than four or five feet, and definately safer than ducking flying objects like galley knives.

Changing clothes is accomplished by lying on the cabin sole. Cooking is done in a crouch or on the knees, so I have yielded to my wife's entreaties to carpet the interior.

There are compensations for all this spartanship. She beats almost into the eye of the

wind, and her low profile/fine entry make it remarkably comfortable going into the short

choppy seas of the West Coast.

After all this eulogizing, you ask, why did I sell her in the first place? It was shamefully

stupid. In a fit of pique following a domestic scene with boat playing the role of mistress,

and loving wife saying, "All you ever think about is that %&!* boat," I put her up for sale.

Months later, restless and disconsolate, I found a nice old sloop which needed tender

loving care, and for several years devoted myself to making her over into a respectable

cutter and a stout singlehander. A larger cutter then caught my eye and I went through

the trauma , once again, of buying and selling. These, too, were wood boats, mainly

because I am a masochistic fool who likes to work on boats as well as sail them.

And finances being what they are, I cannot aford a new Bob Perry or Lyle Hess design

much as I'd like one.

So, in the years following 1971, I would often wander through the marinas of southern

California looking for the familiar white spruce mast with the jumper struts and the

saucy crane head. Some day, I thought, if I ever see that Acorn again, what will I do?

The man I had sold her to had immediately embarked on a ambitious cruise,

destination Alaska. (I has seriously considered Hawaii, but Alaska? Good Lord!).

Somewhere off the coast of Oregon he ran into a brutal storm. He had a fire on board

with the kerosene stove which totally blackened the whole interior. The seas carried away the forward ventilator and reduced his possessions and food to a floating mass of debris bunk-high, I heard later. He turned and ran for home, job, and dry land, left the sloop at the marina and was never heard from again.

Much later I learned that the boat had been sold for back rent and restored painstakingly by a committed sailor into Bristol condition, until his wife uncorked her ultimatum, "It's the boat or me." So once again the little ship acquired a new and affectionate owner.

In the late summer of 1977 I had a vivid dream one night in which I spotted the familiar mast in a marina. Waking with a start, I felt it had to be an omen after all those years. I told my spouse and she most generously said, "Well, you always loved that boat. Why don't you follow your hunch and see if you can find her?"

We had just sold the big cutter to help with some family needs. I had a modest cash reserve and I was once again boatless. That is a challenge to the sailor. So I set out on a serious search, sneaking in through gates, waiting for people to open them, climbing over them like an aging thief. I drove and walked for miles.

On the fourth day I re-lived the dream. Could it be possible that this familiar mast I observed from afar was real? Chafing, I waited at the gate until someone let me in, then ran down the dock in apprehension. She had been so altered that I had to inspect the CF number to be sure, but yes, this was EIGHT BALL alias LITTLE JOSIE alias how many other names, heaven only knows.

And I, a grown man, stood gazing at her with tears streaming down my face in a welling-up of remembrances. Days and nights andweeks on end sailing the Pacific with her as my only companion. Being down below reading or sleeping or making soup while she obediently held her course with a piece of shock cord at the helm.

Now she looked unbelievably small. Had I done all that cruising in this tiny craft and come home again and again, safely?

With trembling hands I penned a note to the owner on the back of an envelope and stuffed it through the hatchway. I told him this once had been my boat and asked him if he would consider selling it to me now.

Next evening he called, astounded at my story. Did I really want her back that badly? Of course. When your heart is on your sleeve, you're in no mood to dicker. We met at the harbor the next day and he described how fond he was of her but that his family was simply too tall and too numerous to share her space-capsule accomodations. They wanted a bigger boat.

So it was done.

Now I am the soul of content, hoping that this time I can stay that way. Why is it that men must forever be questing and searching, and malcontent? I had to go through all of this to come back to dead center. I should know by now that every boat has virtues and faults alike, that each selection we make is a compromise. Rising costs of dock fees, parts, equipment all have a bearing on what we sail and what we logically should stick with. True, some bigger boats are a good investment because they gain in value as labor and materials soar to new heights.

It is strange. I am no longer a young man, but the fires of adventure still smolder within, and I still dream the improbable dreams of faraway shores and the lengthy sojourns on the ocean that renew the soul.

It may yet pass that I can write for you some interesting accounts of how LITTLE JOSIE and I made it across the Pacific to legendary lands that so few of us are privileged to see. Having once sold my sextant and the Sailing Directions of the Pacific Ocean doesn't mean that I have truly given up. One must never give up. You have to keep the dream alive, for that is the elixir which sustains us through all the other impediments of life.

One day I will own another sextent and a good weather radio, and I will send you an adventurous account from the lands below, from a very small and adequate boat I have learned to trust, and I will be treating her with the deferential and circumspect devotion to which a lovely little lady is entitled.

May you also find the boat of your dreams and hold onto her for dear life. It may mean making the most of what you already have, but in an ensuing article I will try to advise you on how to do just that.

C.H. (Bob) Andrews is a writer, former newspaper publisher, and a veteran of much solo ocean sailing. His ambition is to sail LITTLE JO to Australia. "She'll do it," he says, "the biggest obstacle is me."

The Story

In 1977, Wooden Boat Magazine published an article by C.H. Andrews entitled "Before You Let Her Go". When I was preparing the first generation of this Web Site I approached Wooden Boat for permission to reprint the article. Unfortunately they couldn't give it because their copyright processes in the early days had not been properly sorted out. Mr. Andrews accordingly held the rights, and I eventually managed to find him and obtain his consent to include the article below. The colour photos were not part of the original article, but rather from Bob Andrews personal collection. Hope you enjoy the article, and can better understand why I started this project. PS

In 1977, Wooden Boat Magazine published an article by C.H. Andrews entitled "Before You Let Her Go". When I was preparing the first generation of this Web Site I approached Wooden Boat for permission to reprint the article. Unfortunately they couldn't give it because their copyright processes in the early days had not been properly sorted out. Mr. Andrews accordingly held the rights, and I eventually managed to find him and obtain his consent to include the article below. The colour photos were not part of the original article, but rather from Bob Andrews personal collection. Hope you enjoy the article, and can better understand why I started this project. PS